At the Hospitality Hub in Memphis, we are steadfastly committed to facilitating transitions out of homelessness. By providing comprehensive support services from a single, safe location in downtown Memphis, we have been working to assist those experiencing homelessness with temporary shelter, identification acquisition, employment opportunities, and more. However, as the issue of encampments has become more pronounced, our approach needed to adapt. Teaming up with Dragonfly, a local social impact firm, we embarked on a journey to not only provide immediate relief but also address the root causes of the encampment problem. Forbes recently shed light on our endeavors and the collaborative measures we are taking to ensure a holistic, compassionate approach to the multifaceted challenge of homelessness. Dive into the full story to learn more about our methods, experiences, and vision for the future.

Tennessee Encampments: “This Is A Solvable Problem.”

In this post, I’m following up a post last week about Tennessee’s challenge with a law banning camping on public right of way. I had a dialogue with Jarad Bingham principal atDragonfly Collective in Memphis who I have interviewed in the past about his work in Memphis addressing the needs of unhoused people. Bingham has worked over the years to buildthe Hospitality Hub, “a holistic approach to helping individuals transition out of homelessness.” In that post, I noted that, “In Seattle, the divide is roughly between the “sweep ’em and lock ’em up” crowd and people that mindlessly defend the status quo because it is “compassionate” and feel it is wrong to force norms on people in the encampments.”

I also noted how much I appreciated “Bingham’s nuanced views and work are what’s needed in the tangled web of politics and inflationary policies that are neither effective nor edifying.”

Recently, his organization managed to tackle a local highway encampment effectively with just such nuance. Using outreach efforts and expertise, workers from the Hospitality Hub began slowly moving people out of encampments on highway right of way. There was a pressure to move; the camps were going to be cleaned up. But the Tennessee Department of Transportation gave workers from the Hospitality Hub passage to use their skills and the knowledge they gained from working with individuals in the camps.

Bingham finds that a leading problem to moving people out of encampments is high barrier, congregate shelter. Often, people living in an encampment on the right of way, or anywhere, are doing so precisely because they can have freedom and privacy, something valued by everyone. Bingham’s outreach workers ask what is a basic economic question: “Is there any place you’d rather be.” Listening to the answer and responding, along with supportive case management to address underlying addiction mental health issues, has become an abiding principle in the work of clearing encampments.

How about some background. What got you motivated to address the encampment issue?

We spent a lot of time thinking about encampments. I went out to LA and visited the one from the cover of Harpers– they had three tents illuminated from within and the text, “Where Would We Go?” I visited San Francisco. We wrote a pro forma for a managed site with tents in Memphis, (I was going to ask North Face to sponsor us). We did put hammocks in our plaza, which is a beautiful urban park without some of the invisible barriers that civic space can have. But in the end, we just couldn’t get comfortable with the idea that some people need to be sleeping outside. Once that was off the table, we got to work designing better solutions.

In the last post, I outlined what appeared to be an intractable problem in Memphis and in other places in Tennessee; a new law made camping or living on public property not only illegal but a felony. What led to this law and do you agree with it or disagree with it? Why or why not?

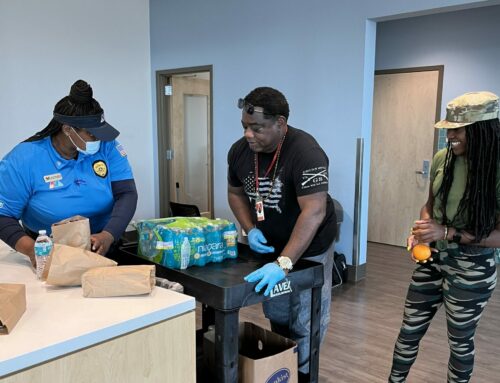

Let me quote a doctoral candidate at the University of Memphis who came to work with us this Summer. His name is Sharif Hossain, and he is from Bangladesh. His first day with us we had him sit at the front desk on our primary campus and watch people come through and be greeted by Terri Conley’s giant smile or Sam Smith’s comforting eyes. He had a couple of Masters degrees, one in public policy, and I had briefed him on our programs, but when he saw the way human centric design embodies the program elements on both sides of the desk, he was inspired to find me and tell me about why it was so meaningful.

He said that “homelessness is America’s shame,” and I think he’s right. The context for the Tennessee law is the existence of extreme poverty and of literal homelessness and the prevalence of panhandling and the growth of encampments in cities across the country. People are ashamed, both the people living outdoors and the people who walk or drive by, and that shame drives anger or compassion or any number of easier things to feel, including new legislation. Agree or not, the TN law is policy reality now, and the new question is “how do we manage compliance on this new policy initiative?”

Do you think the divide between people who want to, reasonably perhaps, enforce the law and those who favor less intervention has gotten worse? Why?

In one way the law gave substance to anxieties on a continuum of concern for and against people sleeping outside or just being visibly poor outside, but I have not noticed a stronger divide. My experience has been that there are always people against what you do. It is safer to not do than to do. Even now that there is a law, there is a resistance to enact it.

Let’s get specific. You had the City pointing at the State, and the State pointing back at the City. Why did you want to get into the middle of that?

For a lot of reasons, but the through line is that our organizational value is derived from our capacity to solve extremely difficult problems. At the micro level, we are experts at co-developing paths out of homelessness for the endless variety of individuals who seek our help. One click further out, we design nuanced solutions for gaps left by HUD program compliance, and we partner with government, NGOs and philanthropists to fund most of our pilot and long term projects. We provide an important service for maintaining the civic commons. From here it’s easy to see how we’re implicated: our people are the ones living outside, and our partners are the ones stalemated in the search for a solution. Public pressure was mounting. You’re exactly right, I did want to get in the middle of it.

What was the solution and approach to untangle this?

It was a two-part solution, and one part we already had. We had already built an Outreach team, led by Liza Hubbard, who is the embodiment of wisdom from our organization in the field. Under bridges. Deep into forests. Following up on people in hotels and when they get out of treatment and doing all the remarkable work to find people where they are and help them make a solid step away from living outside. We run 120 hours a week, all day, every day, snow, ice, like the mail used to be. Liza’s team and our organization’s thought-out discomfort with encampments is why there are relatively few tent encampments in Memphis today. This interview is about sites on State right of way, which is beyond the control of the City, and therefore beyond our set of permissions.